When Sebastian Thrun gave an interview about Udacity on NBC, he dodged a question.

Isn’t Udacity bad for professors?

The interviewer repeated it a few times, and each time Thrun gave the weakest answers of the interview. This is unfortunate, because there is actually a really good answer.

The question comes from a misunderstanding of what professors do all day long. Because teaching is the most public part of the job, many people assume that it is the most important or the most enjoyable. And, for a select few professors (some of whom I was lucky to have in class), it is. However, lots of professors get into the profession because they love research and discovering new things. Others love nurturing a few bright students, or holding vibrant discussions.

Unfortunately, professorship thus far has been a take-it-or-leave it package of lectures, grading, mentorship, study, and bureaucracy. Ask a professor which part of their job they love most and they can tell you. Ask which part they hate most, and they’ll also tell you. It’s different for every professor. Very often it aligns with what they’re good at and what their students and research funders benefit from most. Still, they are forced to do those other parts of professorship because that’s what being a professor is.

Adam Smith would throw a fit.

Udacity allows for a division of labor, and that is good for everyone.

You love teaching? Great, go work for Udacity and you can reach millions. Hate teaching? Great, you are now free to pursue your research uninhibited while your students complete Udacity courses far better than whatever lecture you would have prepared.

More learning from students. More research by professors. Everything is better. So why would anyone oppose this?

The funding model.

Udacity is good for everyone except third-tier universities.

These are institutions whose business relies on people paying large amounts of money to sit in a room for a few hours then receive a piece of paper at the end. This works because students think they have no other choice. Now they are learning that they do.

Stanford has nothing to fear because the Stanford connections are valuable even in the absence of the classroom. High-quality second-tier institutions have nothing to fear because the personal attention the students receive beats anything an online course could give. However, many institutions will die, and that is okay, because they were the ones not worth saving.

A new study shows that people are happiest when they keep busy but do not feel rushed.

This has explanatory power for two distinct phenomenon.

Why commuting sucks

The happiest state is when you are busy but not in a rush. Its opposite, the state of feeling rushed but not keeping busy, is uniquely unpleasant. The two examples that spring first to mind are 1) waiting in line and 2) commuting.

With commuting it’s bad enough that you have to sit in a car, sometimes stalled by traffic, severely limited in what activities you can undertake… you also have a deadline. You are rushed without the ability to make up for their time crunch except for speeding and, in traffic, some dangerous maneuvers.

People take these maneuvers, of course. This state is so unpleasant that people are willing to risk their lives to escape it. Less obvious, but almost as dangerous, are the methods that they use to avoid not being busy. Some, like music or audio books, are relatively harmless. Others, like putting on makeup or texting, are known death risks.

So yes, this state is bad. People would, almost literally, rather die.

Why people love World of Warcraft

On the other end of the spectrum are activities like World of Warcraft. There are always more things to do, but there is never any rush to do them. Happiness dream.

There are other reasons people love it, of course, and many reasons why it can be an unhealthy habit, but the boost in happiness caused by having a full but unrushed life is enough to overcome an addict’s doubts.

But wait, there’s more!

How can we use this to shape life to our advantage? Online pursuits, though rarely as satisfying as their real-life counterparts, offer the advantage of convenience. Not convenience just for the lazy, but convenience for those who wish to avoid a happiness-destroying commute. Faced with the choice between a mix of sharp pain and sharp pleasure vs a dull pleasure, many choose the dull pleasure. Yet what’s good for facebook is not necessary good for civic life and human happiness.

This study is yet one more reason to cut out the car-bound suburbs (and all the waste it brings), then pack and shrink our cities until travelling (walking) to your events is almost as pleasurable as getting there.

Like many things in modern America, “regulations” have become a sort of litmus test for which of the two giant gangs that you belong to. More regulation? Democrat. Deregulation (less regulation)? Republican. Reagan is famous for deregulating large swaths of private industry, greatly reducing the amount (and severity) of rules they had to follow, and Republican congresses have been highly vocal in fighting regulation pushed by Democrats.

However, this divide ignores the fact that “regulations” aren’t just a homogenous mass who volume should be either increased or decreased, depending on your political affiliation. There are good regulations, bad regulations, and regulations that are of mixed effect (good for some groups and bad for others). Most, in fact, are of mixed effect… although sometimes the group they benefit is very small and the group they hurt is very large.

Special Interest Regulation

These types of regulations are generally lobbied for by the small group that they will benefit and ignored by the masses who will suffer under the terms of the new regulation. The trick to this type of regulation is that there is a large benefit to the well-connected few while the amount of harm caused by the regulation to each individual outside the favored group is small enough that it barely crosses their radar. Nonetheless, the total harm caused is greater than the total benefit.

One example, given in Jeff Speck’s wonderful book Walkable Cities, is that of the mysteriously wide Miami intersections. Two narrow streets in residential neighborhoods will inevitably meet in an overly large block of asphalt. This asphalt cost money to build, trapped heat, inhibited walkability, gobbled up real estate, and required even more money to maintain. So why are they all constructed like this, when there is a large public cost and no clear public benefit?

The answer is that the firefighter’s union once struck a deal that no truck would ever be sent out with fewer than four firemen on it. That’s good for safety and even better for job security, but the only truck that seated four was the hook and ladder. So, for many years, one-story residential neighborhoods in Miami had to be designed around the lumbering turning radius of a truck built for tall-building fires. —Jeff Speck

The firefighters benefitted greatly while the rest of the population suffered the minor collective expense of more taxes and decreased livability. I choose this example both because it deals with my favorite subject of walkability and because it implicates a type of person we usually hold up as noble. If firemen can come up with regulations this self-centered and wasteful, imagine what is being done by the less trustworthy and less heroic special interest groups in our communities.

Anti-competition Regulation

A subset of special-interest regulation is monopolistic regulation. Imagine that company X and company Y are in competition to build ladders. Company X has a patented system to provide “finer grained height control” by placing the rungs at the top of the ladder closer than those at the bottom. Company Y makes ladders with rungs that are evenly spaced the whole way up, and is losing in the marketplace because users prefer company X’s patented “finer grained height control”. For a relatively small cost, company Y can lobby for “safety” regulations that require ladders to have evenly spaced rungs, thus destroying company X’s advantage and nullifying the value of company X’s entire stock of ladders.

This is a made up example, but favorable regulation is an obvious method of gaining a market competitive advantage. Based on the number of lobbyists in Washington, it is a method that is being fully taken advantage of.

Good regulation

Good regulation is that which preserves shared resources, protects the basic rights of citizens, and promotes honesty in commerce. These are purposefully fuzzy categories which each merit (and have received) multiple books on the subject, but of particular interest in this case is that of protecting shared resources.

Regulation to protect shared resources, besides ensuring the health and continued wealth of each individual citizen, can be seen as an extension of both property rights and criminal justice.

Property Rights

If a resource is shared and someone degrades it, they are depriving you of the value of your portion of the shared resource and thus owes you recompense for the destruction of your property.

Criminal Justice

If I punch your child, I will rightfully go to jail. However, if I contribute to pollution which causes your child to have asthma, it is the job of the regulators to either make me stop the harmful behavior or make me pay a cost proportionate to the harm caused to others (and then use that money to help the victims). Money, of course, cannot make up for the tragedy of a perpetually ill child, but it at least sends a signal to the offending company and helps those affected to make up for their loss.

Tragedy of the commons

The tragedy of the commons, in the original example, concerns a public pasture on which cows can graze. When a cow grazes on on the pasture, it reduces the level of the grass available and eventually degrades the quality of the land itself through overgrazing. This reduces the quality of the grazing for every cowherd, including the one who owns the cows doing the destruction. However, despite the damage being done to the pasture, there is no point before the complete destruction of the commons at which it is to the advantage of an individual cow-herd to stop using the “free” grass and start feeding his cows on his own land. Thus all the cowherds put all their cows on this one common piece of land and it is (tragically) destroyed.

This is both the peril and promise of regulations.

The peril: Special interests groups create regulations that benefit themselves greatly but hurt everyone else either directly (anti-competition), indirectly through wasted resources (the Miami residential intersections), and indirectly through increasing the amount of red tape that everyone must cut through before starting a new venture.

The promise: Our air, water, and land are textbook examples of the tragedy of the commons. The actions taken by polluters result in decreased health and increased cost (filtration systems, medical bills, etc.) for everyone in the affected area, but it is never to the immediate advantage of the offenders to stop polluting. However, smart regulation can put the cost of pollution on the polluters, making the market fair again and helping to preserve the shared resources that we all rely on.

This week I pushed out a lot of half-baked articles and two gems. That’s not to say that the other five articles were bad; they were thoughts I wanted to get out, and they were written pretty well… but they went almost straight from my brain to the page, with only a few quick information grabs in between. Here are the four things I’ve learned from my first week:

Planting: 4 minutes

A picture of a main standing on a mountainside, sun bright behind him. “A sun ray on a cloudy day makes me smile“. Sonreir. To smile. I’ll practice this word six times before the session is done, but for now I move on to the next word. Feliz.

The memory trick (or mem, presumably short for meme) attached to feliz is a festively dressed cartoon hispanic rodent, looking very happy and yelling “Feliz Navidad”. It doesn’t quite make sense, but the unusual image — combined with my familiarity with the phrase feliz Navidad — does a pretty good job of keeping the word in my head.

I hit enter, and I’m presented with four different spanish words. I have to choose the one that means ‘smile’. Sonreir. I select it, hit enter, and move on. I will see that word five more times today.

There are some pretty good reasons to nap

Let me list some:

- Better memory

- Better mood

- Decreased stress

- More creativity

- Increased Alertness

- Increased muscle repair

- Reduced fatigue

- Decreased risk of dying (down 64% in working men)

- Better performance for astronauts (the NASA study did not cover other professions)

But you don’t.

Because your city (not to mention your job) isn’t built for napping. Read more…

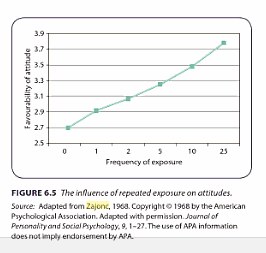

The familiar is comforting. Fact. Popularized by Robert B. Zajonc, social psychologist, in 1960s.

In one experiment, he even showed that you can be made to like chinese symbols you don’t understand just by looking at them a few times. Here’s how that went down.

Seeing is liking

He took 12 chinese symbols, and started showing them to the subjects. An “exposure” was two seconds of passively looking at the symbol, and the subject was exposed to each symbols somewhere between 0 and 25 times. Then, Zajonc asked them to rate how positive the meaning of that word was. It turns out, the more you are exposed to a meaningless symbol, the more you like it.

Selling horoscopes brings in scads of money, but they’re mostly bullshit. The typical horoscope is generalized life advice, seemingly made relevant by the Forer effect. Even if you believe in astrology, the majority of horoscopes peddled aren’t even accurate by astrological standards.

Myers Briggs is a psychological system for typing people into 16 categories on 4 axes. Introvert/Extrovert, iNtuitive/Sensing, Feeling/Thinking, and Perceiving/Judging. I am Extroverted, iNtuitive, Thinking, and Perceiving, so in Myers Briggs Parlance I am an ENTP. The type is also called the “visionary”, and other ENTPs include Steve Jobs, Richard Feynman, and Tony Stark. Myers Briggs is not perfectly accurate, especially for people who are on the borderline (I am on the border between introvert and extrovert), but it is good enough to be psychologically useful. And, anecdotally, I idolized all three ENTP examples before I knew I shared their type.

So, we have a personality test that is reasonably accurate and a large, profitable industry based on giving life advice. What if we combined the two? Gave advice that is specifically tailored to that personality type. An ENTP (a visionary who gets excited by new ventures) would get told to make small bets before jumping off the deep end, while an ISTJ (a duty fulfiller who takes rules seriously) may get reminded that the most important rule is forgiveness. So that’s the market: people who want personalized daily advice.

The business part would be to give away one horoscope per week, then charge a small subscription ($5/month) to get one every day. The costs would be advertising, web hosting, and writing. Web hosting is ridiculously cheap, writing can be done by yourself, and advertising can either be foregone, or you can make sure that the advertising pays for itself.

Now go get entrepreneuring.

It’s not real yet, but it will be, and it come surprisingly close to my ideal living space. You can read the wired article on the web urbanist article for details.

Given that half of this map is green, you might be surprised to note that this will be six times denser than london.

My thoughts?

Obviously, they designers of this city have spent a great deal more time thinking about the design than I have, so I want to know their reason for making the city fit 80 thousand people. My ideal living space is also a very dense urban core with surrounding green space, but each is much smaller. I would like for each city unit to be small enough that you can recognize most of your fellow residents on sight, and have a sense of common identity. 80k is big enough for empathy fatigue to set in rather quickly.

It’s likely that the designers did not have the idea of a cohesive community as a primary goal. Their main goals were efficiency and a pleasant living area, which they have (theoretically) accomplished, stunningly so. A fortunate side effect of this will indeed be a slightly better community, but not nearly as much as if they had made that one of their core tenets from the start.